The history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) is frequently told from the perspective of those who consider its end to be the all-defining fact of its history. From this angle, the complexity of the various opposition movements in the GDR appears unimportant for the historical understanding of a state which, according to this logic, was always destined to fail. Even though it may be difficult in retrospect to imagine a different outcome than so-called German unity, toppling the government was far from the only political goal of the GDR’s oppositional citizens. A number of them organized around environmental issues, others for peace, and a large majority were interested in several of these overlapping political aims. The focus on the large civil rights movements that were most active immediately prior to the historic upheaval of 1989–90 fails to consider many other constellations and approaches. An expanded examination of the history of such movements must therefore consciously distinguish between student resistance, engagement in political parties, dissidents, environ- mentalists, the peace movement, the women’s movement, and oppositionist activists within the leadership of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (Socialist Unity Party of Germany) (SED) as well as the church.

This conversation with literary scholar and cultural scientist Peggy Piesche, carpenter, author, and chartered engineer Samirah Kenawi, and HKW editor Eric Otieno Sumba explores the inner life and points of contact between different oppositional movements in the GDR on the basis of the personal experiences of two contemporary witnesses. Piesche and Kenawi were both active in the peace, women's, and lesbian movements and since 1990 have engaged in a critical examination of their own history within these movements in the context of the GDR. In the conversation it becomes clear that movements in the GDR were always dynamic.

Eric Otieno Sumba (EOS): What personal connections do you have to the opposition movements in the GDR? And which movements were they?

Samirah Kenawi (SK): I was active in various groups within the women's and lesbian movements and after the fall of the Wall I attempted to preserve the traces of these movements and make them visible. I did this, on the one hand, for the protagonists themselves, and on the other, to facilitate a discourse within the West German women's movement, in order to show the different scopes for action, themes, and perspectives that we had. Through this retrospective archiving of the movement, I have gained insights that I didn't have as a protagonist in the GDR. I have discerned connections that have only become understandable in retrospect.

EOS: Peggy, what was the situation for you?

Peggy Piesche (PP): I come from the provinces. I was born in Arnstadt, a small town in Thuringia. Unfortunately, during my childhood and youth I had very little contact with other Black people. However, as a young person I was active in the peace movement. That was also in the somewhat provincial areas, however I was able to gain a number of insights into the movements in the GDR-also with respect to their limitations and the repression that went hand in hand with them.

EOS: What were the motivations for your activities in these movements? Were there politicizing moments of awakening or key historical events?

PP: It wasn't historical moments for me, because there simply weren't any. It was far more to do with biographical moments. I completed the 10th grade at a polytechnic secondary school, after which followed my first political entanglements, or rather, I came up against the limits or perhaps the preliminary limits of this state. Initially I wasn't allowed to continue to advanced secondary school meaning I wouldn't have been able to do my Abitur (high school diploma). Only through the decisive intervention of my mother, a worker, who went to the district council and said very directly that this decision was racially motivated, was I allowed to undertake vocational training that encompassed my Abitur studies. That was an initial process of loosening the ties. In other words, I have to answer your question biographically. I went to a boarding school in Gotha, where I worked in an LPG (Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaft or agricultural production cooperatives} and completed my vocational training with my Abitur. It was important for me to find a means of dealing with the experience of being 'made other'; in other words, racist experiences in the GDR, even though I didn't have this term at the time. It was clear that I needed space in which to reflect on this experience, because I realized quite quickly that if I didn't do this, then I would end up accepting these external ascriptions. I had a very clear need, a very clear impulse not to do that. Unfortunately, as I didn't have any contact with other Black activist groups in the provinces or any kind of movements that only happened after the Wall came down. However, the peace movements, which were primarily anchored in the Protestant church, provided a space in which I could meet people with similar experiences. The church context didn't interest me, and that was okay, as it was very clear that it was a youth movement. And in my case I encountered something there that was also political. In this context it also provided space for young people who shared experiences of being 'othered', even though they were white young people. They wanted to live a different life or knew that something else had to be possible. That is what fomented my survival drive, which enabled me to grow up in a small town in the GDR in the 1970s. I had a clear compass: something else had to be possible, and I would make it, I would reach the place where this other existence was possible. Today, I would say this is how I survived my childhood.

EOS: Samirah, Peggy mentions the church. In the interview[1] that drew our attention to you and your work, you also speak about the church. What role did it play? Why was the church a place where movements could be active, which otherwise probably would not have been possible?

SK: The church was a place that allowed a certain free space, because there were various connections to the West German church. On the one side, this was as a result of financial subsidies from the West, and on the other, through the global Christian religious community, which created supranational structures that the Protestant church knew how to make good use of. I also became a part of the women's and lesbian movements, as well as the opposition movement, as a result of personal experience, and like Peggy I thought that another form of society had to be possible. This free space in the Protestant church was opened up by an event in August 1976 when pastor Oskar Brusewitz set himself alight in front of the St Michael's Church in Zeitz in order to highlight the discrimination faced by Christians in the GDR.

This led to circulating open letters within the church, which in turn became politicized, initially within the Christian congregations. This resulted in conflicts with the state, which culminated in a so-called discussion of principles between the heads of the church and government leaders on 6 March 1978. This was a completely unique event that had never taken place in this form before or since. At this discussion of principles, the Protestant church succeeded in negotiating a series of free spaces that the various groups could use for their political work. This enabled internal church publication as well as greater freedom of travel for church members. The greater freedom of travel, for example, enabled a relatively large number of women from the GDR to attend the international congresses of the Lutheran World Federation, which, amongst other things, addressed the issue of the role of women in the church.

The situation of women in the church was discussed for over a decade. Christian women from the GDR took this theme into society, which gave rise to the development of a movement of feminist theologians. The Protestant church also succeeded in winning the freedom for church premises to be used by groups, without them having to have their events authorized individually. It must be remembered that the GDR's assembly act stipulated that every event had to be registered in advance, including the precise content, themes, speeches, and so on. These free spaces opened up the possibility for various opposition groups, civil rights groups, environmental protection groups, gay and lesbian rights groups, and women's groups to meet. In doing so they were able to test out a form of semi-public activity, to orient themselves politically, and to initiate opinion-forming processes, which, under the GDR's monolithic unitary ideology, did not exist at all in the public sphere. This allowed a form of opposition movement to slowly develop. However, the movement within these church spaces did not simply appear from nowhere in 1979; prior to this, diverse social groups had been established who could now make use of the semi-public sphere of the Protestant church.

Stand set up by the Lesbians in the Church group at the peach workshop in the Erlöserkirche (Church of the Redeemer), East Berlin, 1983. Photo: Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft / Bettina Dziggel / RHG_Fo_GZ_0396

EOS: What was the situation with the Catholic church? Were there such spaces there too?

SK: The Catholic church adopted the policy of keeping out of things. There were Catholic women, in Magdeburg for example, who were active in the women's peace movement. However, in principle, the Catholic church attempted to avoid all communication with the state. It was the Protestant church that opened its doors politically for an opposition movement-supported by the West churches, financially, but also technically.

EOS: Peggy, were these interfaces between the peace movement, women's movement, and environmental movement already visible to you back then, or have they only become clear to you in retrospect?

PP: The majority of this only became plausible to me in retrospect, when I had more information and could re-contextualize GDR history. That is why I have to emphasize once again that I was brought up in a provincial setting. In 1984, at the age of 16, I set out to discover where there were free spaces. And they tended to be in the Protestant church. During my vocational training this became more virulent. It was like a smorgasbord. In the 1980s, it was about the peace movement, but naturally there were also environmental protection initiatives. It wasn't particularly prevalent for us in the provinces, more so in the industrial areas. However, I have to say that unfortunately I was unable to experience a connection to the women's movement within this context. That only came later.

EOS: Were the terms 'activism' or 'movement' used? What was the perception from within? Retrospectively, it is easy to claim that they were movements, but how did the movements position themselves? Was it clear in what kind of field you operated?

PP: My experience was that it was simple and difficult at the same time. It was simple in the sense that the categorization came from outside. If you engaged with something like women's rights, then that was a form of resistance, something anti-state. 'Activism' wasn't a theme for me, that was not the language we used. Where it was difficult was the question of to what extent do we adopt this categorization imposed from outside? There was definitely a spectrum of consequences that could follow on from this. We didn't see ourselves as resistance fighters, not under any circumstances. I think the common denominator was that it was a movement. This was also something empowering, even though we didn't use the term at the time. In any case, peace movements are something very beautiful. The feeling of not being alone—that is how I would describe it for myself.

EOS: Does that match your experience, Samirah?

SK: I saw myself as part of a movement, because there were numerous groups which we consciously sought contact with. There were various network meetings: staff meetings of the church gay and lesbian rights working groups, various women's group meetings, the meetings of the peace group Frieden konkret, and a network called Frauen fur den Frieden (Women for Peace), which later gave rise to nationwide women's group meetings. So even during GDR times I knew various active groups and networks, meaning I saw myself as part of a movement. The empowering aspect, as Peggy has already said, was to have a space within the monolithic GDR culture and political situation where we could discuss, where there was a diversity of opinions, where there was a dialogue, where ideologies were questioned or even discussed in the first place. As a young person you are in search of all kinds of things. It's extremely important to not be alone in this, but to have other people who you can discuss things with.

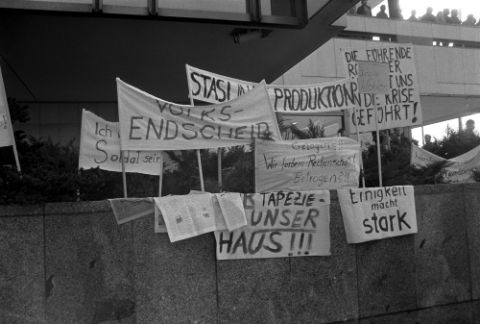

Demonstration against state violence and for freedom of speech and assembly, Mitte, Berlin, 4 November 1989. Stasi Mediathek, signature: BStU, MfS, HA XX, Fo, Nr. 1021, images 2–40, image 4

EOS: This all took place in the context of repression. But when I listen to you it sounds as if you had quite a lot of freedom to articulate yourself politically within these spaces. How did the repression express itself? Did it penetrate these spaces? Was there a fear that fellow activists were passing on information? How did you protect yourselves from being stamped 'oppositional' and the negative consequences of your activities?

PP: Experienced GDR citizens always knew that if three people were gathered together, then at least one person was an unofficial collaborator of the Stasi (state security service). That may sound exaggerated, but we simply grew up with this feeling, it was a form of unspoken self-understanding. Maybe we also spoke in double meanings. Self-censorship can quickly be activated when you know the state is listening. This is something that later generations have to clarify. What I want to say is: I didn't have the feeling that I had devised a good strategy for getting through life in the GDR. Because, as already mentioned, the repression began before this. The experiences that I had in this context occurred on an everyday basis. Amongst other things, I recall we once went to a summer camp and had to fill out some kind of form, like in a hotel today…

SK: Like a registration form?

PP: Yes, a kind of registration form. It was clear to everyone that the little filing cards would be collected and would end up with the Stasi. It was a peace camp of the Protestant church in Rudolstadt, and naturally it was clear that we were under observation. Once we met at the church in Gotha, where a number of people I knew were standing in the courtyard, but also some strangers. I was there with my girlfriend, and suddenly people started photographing us and then someone left. It was clear that they were not from our group. Finally, I found myself in the director's office during my vocational training to discuss whether I should apply to study for a degree programme. The director said to me in plain terms that I was welcome to apply for German philology in Jena, but I wouldn't be accepted. One phone call was enough, and it had already been made. I applied nonetheless, because I was always of the opinion that at least that way they would have to deal with me and be forced to make up some excuses.

It was clear that the state apparatus had to make a little effort to come to certain decisions, in other words to achieve the results it wanted. These were naturally unpleasant experiences, but it was tolerable for me. Some people had very different experiences. It was a little more difficult for my girlfriend. We were put under extreme pressure in the second year of our appren- ticeship, which was crucial for the certificate which you needed to apply to study. This pressure was really hard for her, so much so that she threw in her Abitur. But I knew this kind of pressure from the polytechnic secondary school, I knew what it meant to be 'othered' when something is not permitted under any circum- stances, when you aren't allowed to appear in public. In this respect, I could cope with it well, and apart from that I didn't suffer any major consequences.

SK: Of course I was also continually aware that there was an invisible red line, and that to go beyond a certain limit would be dangerous, i.e., the threat of prison or other forms of repression. I come from Berlin, from an academic family. I was interested in science and technology, and then studied engineering. These were courses of study where access was a bit easier. I know that due to my membership of a group I was naturally being observed, however after my studies I was able to begin a dissertation at the Forestry Institute in Eberswalde. So I didn’t consciously experience any repression, but it was always clear that I had to comply with certain rules, that there was always a limit in terms of political commitment. Within the groups, and especially during network meetings, this was always discussed: Where have new free spaces opened up? How far can one go? We always tried to fathom the invisible border and push it further, for example in Dresden in 1987, when we founded a non-church gay and lesbian working group in a youth club. That was relatively new. So there was room for manoeuvre, but it was always like walking a tightrope. Political engagement in the GDR had a lot to do with personal courage, sounding out and utilizing existing free spaces, and pushing that to the limits.

EOS: Samirah, you said that you knew you were under observation due to your membership of various groups. What groups did you mean?

SK: On the one hand, there was the gay and lesbian rights working group in Dresden, and on the other, later, I was active in various women’s groups and network groups. I was only able to verify this after the Wall fell when I took a look at my Stasi file, but in principle it was clear to all of us that we were being surveilled. Who and how and what and to what extent wasn’t clear to us, but as Peggy said, we were aware that someone was listening, and we tried to talk as if we were in conversation with some state authority. We also wanted to make known what we spoke about in our groups. We accepted this indirect connection to the higher authorities, the fact that someone documented what we were doing. Compared to today, this probably brought a certain sense of responsibility into the groups, a certain discipline during talks and discussions, which was definitely positive.

EOS: Your activity in the summer camp has already been mentioned. In what other formats and in what other places did you meet? And who enabled this, apart from the church? What additional spaces were there to meet, to plan actions? Was it even possible to carry out actions? Did you take to the streets, did you protest?

SK: There were the church spaces, the congregation rooms of the Protestant church of the GDR, where group meetings were held in a certain rotation in various parishes. And there were network meetings where the leaders of different groups met in smaller circles. We also used parish meetings and church congresses in order to voice our concerns in some way. Beyond this there were cross-regional, national meetings where different groups—such as women’s groups, gay and lesbian groups, peace groups, environmental groups, civil rights groups—were active and networked with each other directly. At that time, of course, there was only state-controlled media. Even the church’s information leaflets were more or less subject to the general censorship. So everything had to be discussed verbally, in different formats, which overwhelmingly—I’d say up to ninety or ninety-nine percent—took place on church premises. There were also repeated attempts to use state premises, however they all failed somehow. The Kulturbund der DDR (The Cultural Association of the GDR) had rooms for public events, but just like the Demokratische Frauenbund Deutschlands (Democratic Women’s Federation of Germany) and other mass organizations, it was under the ideological control of the SED. Consequently, none of these rooms could be used by oppositional groups. As I mentioned, we in Dresden managed to organize events in a state youth club. In Berlin, pubs tended to be used instead.

PP: That coincides with my experience. I saw these spaces and groups as educational. As Samirah has already said, we didn’t have any access to media, so we couldn’t spread our concerns or inform ourselves via those channels. Apart from the region around Dresden, we could receive television from the West, and from the end of the 1970s it was relatively normal to consume it. Nevertheless, opportunities for obtaining information via media were very restricted. Plus, this was all before the internet age, where it became possible to quickly Google something. So, in other words, these were first and foremost educational spaces, at least those in which I moved. It was not primarily about organizing a demo or going on the streets because, as Samirah said, there was an invisible red line. Everyone knew that. We possessed an acquired GDR knowledge. No one said: you can go this far and then you go to prison. Instead it was transmitted through experiences. When I did my vocational training with my Abitur, we heard about young people who were exmatriculated and sometimes arrested. This was always in the air, so you really had to pay attention to what was possible and what not. Nevertheless, the church spaces were places where you could find information about climate issues, for example, or the stockpiling of arms in the GDR.

SK: There were also the Protestant academies in all the districts, which offered education programmes that went beyond Christian themes and which we actually used for educational purposes. So yes, there were various possibilities within the Protestant church. Nevertheless, a number of groups attempted to go public outside the church—of course only to a very small degree. For example, the Berlin lesbian group attempted to gain visibility by laying a wreath at the Ravensbrück concentration camp. The Berlin Women’s peace group attempted to generate public attention in a post office through the submission of their opposition to the Military Service Act.[2] And in 1989, following the election on 7 May, there was a chorus of whistles every seventh of the month at Alexanderplatz in Berlin.

The interesting thing about it was that as the Stasi controlled everything, even these small groups were taken notice of and so they had the feeling that they were achieving something. After the fall of the Wall we could demonstrate whenever we wanted, however we soon recognized that though our numbers were far greater-sometimes even a hundred thousand- somehow it didn't interest anybody anymore, it didn't seem to change anything. By contrast, when we went out on the street in the GDR with just ten or twenty people with enormous courage-fully aware that we really could be arrested-then this moved something. In retrospect, it can be seen from the files that the state authorities engaged with the respective issue and attempted to find compromises or solutions.

One example is the gradual liberalization of society's treatment of gay and lesbian people. The file on homosexuality in the Central State Archives of the GDR begins with submissions from lesbians, on the one hand from the Berlin group Lesben in der Kirche [Lesbians in the church] after their actions in the former Ravensbruck concentration camp, and on the other from Uschi Sillge about her endeavours to set up a working group for gay and lesbian rights outside the church. Following these petitions, an interdisciplinary working group was set up at Berlin's Humboldt University. Its foundation and work results are also included in the file. From 1987, the first groups outside the church were formed. In May 1989, the different legal regulations for the protection of heterosexual and homosexual minors were harmonized. Later that year in November, the film Coming Out[3] premiered in Berlin.

EOS: Do you have anything to add about the continuities of these GDR movements up to today?

PP: I have already indicated that my experience of movements in the Black community only began after 1989, and that has to do with my circumstances growing up in a rural region. However-and I find this very symptomatic-from 1990 I was also able to establish connections with other Black people from the GDR. It was not only nice, it also meant I felt a connection to my former self, to the GDR-me, also getting to know Black lesbians and finding out, in retrospect, what was possible in the GDR. In fact, the GDR in all its homogeneity-and it was drowning in homogeneity-was more diverse than it wanted to be. Above all, this revealed itself to me when I got to know these other people.

SK: Personally, I didn't experience any racism in the GDR. On the one side, that naturally had to do with the fact that my multicultural background tends to be revealed in my name, and less through my appearance. It also has to do with the fact that my father died young, and subsequently I didn't have any contact with people who came from multicultural households, so I actually grew up very 'German'. My mother and my social father were German, meaning that I was only introduced to German culture at home. It was only in retrospect that I found out how much racism there was in the GDR. I was really shocked. That had—as far as I could see—a lot to do with labour migration. My father came to the GDR as a student from Egypt, and in my seminar group there was a Black woman who came from a similar background, as there were many international students in the GDR in the 1950s and 60s. Academics were far more likely to be integrated into GDR society than people who came to work and were instead quite marginalized, which was a huge problem. You have to take a precise look at people's different backgrounds when you address racism.

PP: I would also like to add that this was also very much dependent on where a person lived in the GDR. What you have just pointed to, Samirah, is that in the case of what we would now call BIPoC migrants, there was, in a certain sense, a first class and a second class. These are distinctions which were not communicated at the time. What became shockingly clear to me in retrospect-to put it briefly-was that this categorization was oriented according to the position of the respective country of origin within the Cold War. This also determined what type of education people received in the GDR or what kind of work they had to do. Countries oriented towards the West had to pay for the training of their young citizens with foreign currency. The GDR desperately needed this. In principle it was about US dollars, i.e., hard currency, while students from the so-called young socialist nation states received a free education. That always proceeded in the name of international solidarity, however, ultimately, this meant that the young people had to be available for the labour market in the GDR.

The treaties with other countries were determined by the economic needs of the GDR, which as we know were very great. This led to cases such as young people from Mozambique receiving their training with the GDR's state railway or in brown coal opencast mining, which definitely wasn't much use to them in Mozambique. The other thing I wanted to add is that one of the few opportunities I had to positively negotiate my own identity in the GDR was when I was in contact with the contract workers in Gotha who worked in the LPG. Those were important moments. However, these were separate spaces; the spaces of the peace movement and the church were something else. That is why, in the period between 1984 and 1989, it was incredibly important to me that I had contact with contract workers from Zimbabwe, Angola, and Mozambique while I was in Arnstadt, Gotha, and Erfurt.

Translated from German by Colin Shepherd

[1] Veronika Kracher, 'Sexuelle Emanzipation gehorte nicht zum Programm der Arbeiterbewegung [Sexual emancipation was not part of the labour movement's programme]', L-Mag, September/October 2019: www.l-mag.de/aus-dem-heft-1015/sexuelle-emanzipation-geho-erte-nicht-zum-programm-der-arbeiterbewegung.html.

[2] Editorial note: In 1982, a new Military Service Act was passed in the GDR which, in the event of a mobilization, stipulated that women would also be called up for military service. In protest against the law, women's peace groups formed, primarily in Berlin and Halle, which pursued various forms of action such as collecting signatures, organizing peace workshops, and evening prayers with a political subtext.

[3] The feature film Coming Out (9 November 1989) tells the story of a young gay teacher in East Berlin. It was directed by Heiner Carow and produced by the DEFA Studio for Feature Films in Babelsberg, Potsdam.