Bitterfelder Weg and Migrants Across the Artist-Worker Divide

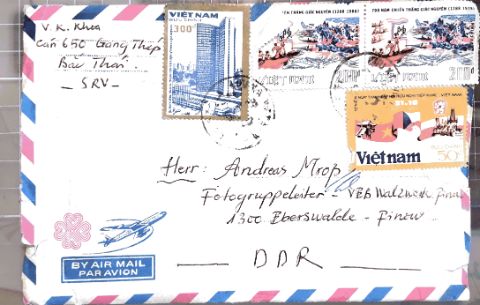

Envelope of a letter sent from Vietnam by Vũ Kim Khoa to Andreas Mroß, re-establishing their contact with one another in 1988. Courtesy of Andreas Mroß

In 1955, workers wrote an open letter to various writers of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), in which they demanded that they write more books about the lives of workers and their contributions towards building a new society. The Bitterfelder Weg initiative led to a fundamental shift in the cultural policy of the GDR. Not only did writers go into the factories to learn and write about workers’ lives, the policy also promoted art by workers themselves. Professional artists formed numerous artistic circles in the factories, ranging in mediums from writing and photography to painting, theatre, and dance. The Bitterfelder Weg, named after a writer’s conference in 1959, bloomed as a cultural movement that aimed to bridge the gap between the arts and the factory, and to establish workers as cultural actors.

With the establishment of these artistic activities, critical views of and from the GDR emerged. The Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (Socialist Unity Party of Germany) (SED) however conceived of the initiative more as a tool to promote socialist party politics which was reiterated in the second Bitterfelder Konferenz (Bitterfeld Conference) in 1964. The party wanted the Bitterfelder Weg to serve as a cultural policy and ideological instrument of state socialism, and critical voices calling for the autonomy of art were not appreciated. Artists and cultural workers criticized this instrumentalization and regulation, asserting the critical function and social responsibility of art.

As a result of the Bitterfelder Weg, writing circles, workers’ theatres and cabarets, and folk-dance groups were founded across the GDR. Artistic practices and cultural activities were made accessible across social groups and generations, and participating artists were often dedicated to bringing their arts to a general public. The results were presented at the so-called Arbeiterfestspiele der DDR [Workers’ festival of the GDR] and popular works by famous GDR writers such as Christa Wolf and Brigitte Reimann drew upon their time spent in the factories.

Through the lens of Echos der Bruderländer, researcher Nguyễn Phương Thúy sought to assess whether these artistic circles were as accessible to contract workers as they were for their GDR co-workers. Engaging with the Archiv der Schreibenden Arbeiter*innen [Archive of writing workers] and speaking with several GDR artists who were facilitators in these circles, such as photographer Andreas Mroß, painter Sigrid Noack, writer Rüdiger Bernhardt, artist Reimar Börnicke, or choreographer Dina Wust, it appears to have been an exception rather than the norm. Although they reported that the workers’ festivals featured international presentations and artworks, it remained unclear if they were by contract workers. However, as can be derived from this community-driven research, art and culture, especially music and poetry, were a crucial part of the diasporic working classes in the GDR.

In this section, visitors are invited to engage with personal accounts and works of former contract workers from Algeria and Vietnam. Some of them were sent via an open call on Facebook and others through direct personal contact. Other contributions were found through community events and personal conversations. The material includes designed and embroidered articles of clothing that workers would sell to other colleagues or wear themselves; letters and lyrical pieces sent to lovers, family members, and friends; and paintings and poems produced to record youth and life in the GDR.