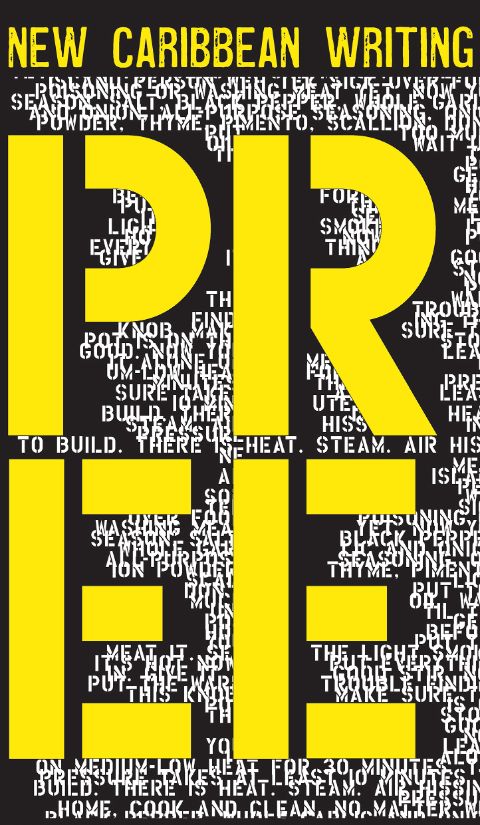

A Statement from the Editors and Founders of PREE: Caribbean Writing

Annie Paul, Isis Semaj-Hall

Free to live. Free to yes. Free to no. Free to love. Free to bumboclaat be. This was how we began the editorial note for issue 4 of PREE: Caribbean Writing, themed ‘In a Free State’. To that statement we now add free to write, free to create, free to travel, free to free—the verb ‘write’ encompassing a range of expressive genres from text to video to sound work to visual art and any medium Caribbean folk choose to feature in PREE.

For the last one hundred years, writers from Haiti, the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Cuba, Jamaica, and all across the region and its diaspora have used their words to raise awareness of important issues such as colonial oppression, gender inequality, alienation and identity, and environmental degradation. Artmaking in the Caribbean has never been devoid of the political, and language is the most important frontier left to breach, with the creoles and patwas of the region laying waste to the stiff, starched official languages the Europeans left behind. From its inception, PREE has been a conduit for new forms of writing on and from the Caribbean and on our platform you will find a variety of Caribbean vernaculars styling themselves.

As our editor Isis Semaj-Hall observes in her essay ‘A Brief History of the Word “PREE”’, ‘PREE has a way of capturing an intent of both the speaker and the listener, the writer and the reader. Any English-speaker can signal the introduction to something new by saying “look!” or “listen!”, but there is something uniquely Caribbean about the contemporary usage of pree as an attention-grabbing verb. PREE locates the user as Caribbean with an intent to share observations, provocations, and understandings of the Caribbean world’.[1]

When a small group of us started PREE in 2018 our objective was to intervene in the literary ecosystem of the Caribbean in ways that new and emerging writers, especially in the Anglophone Caribbean, would find supportive and generative. What, we asked ourselves, was missing from the literary landscape?. There were hugely successful literary festivals, several well-established writing workshops and residencies, prestigious prizes, and awards—but where were the literary outlets?

If one wanted to point agents, editors, and publishers toward emerging Caribbean writers and their work, where could one send them? This is the lacuna we have tried to fill with PREE, an open access, born digital, magazine of contemporary writing from, on and about the Caribbean. Our aim is to be a mothership for Caribbean creativity of a certain kind, a vehicle for Caribbean writing of substance and quality.

PREE’s project is not so much the writing of ‘West Indian literature’ (the preoccupation of previous generations), as it is telling Caribbean stories or storifying the region. What does the writerly gaze look like almost three decades into the twenty-first century? Is new writing animating our Creolescapes? Are there new horizons of readership and writership? In what tone of voice and in what accents do we write the archipelago? Can it be written as it is spoken? The range of creole expression in each of PREE’s issues vary in inflection from island to island (a significant challenge when it comes to copy editing such material), producing lively depictions of life in the Caribbean and the new worlds conjured by languages that arose to bridge difference.

Although the initial heavy-lifting was done by Jamaican or Jamaica-based writers and publishers, we then invited editors and writers from different Caribbean locations to join PREE’s editorial team. For geo-linguistic reasons we decided to focus on the Anglophone Caribbean, not wanting to strain our capacity limits or bite off more than our Anglo teeth could chew. IF we survived, IF we thrived, then we could consider expanding our linguistic limits.

PREE emphatically occupies the middle ground Chinua Achebe invoked, that ground which is the present, not the past, not the future, but the present. The virtual space we offer is also a middle ground between the inner and outer Caribbean, the region, and its diasporas. We are a friendly waystation available to those embarking on the lonely, arduous journey towards a writing life.

Writing itself is a practice that renders an often hostile and bewildering present scrutable. The poet Kei Miller recently observed that we live in a polarized world where it is harder and harder to find a middle ground in the free-for-all between extremists on various sides of the political and social spectrum. This is the ground good writing provides, a space in which to shelter from the harsh black and white palette otherwise on offer.

It is our pleasure and privilege therefore to bring the exuberance of Caribbean tongues and tales from our digital platform to the live stage of HKW’s Middle Ground programme taking place in Berlin. Give thanks to the HKW team for this invaluable opportunity.

[1] Isis Semaj-Hall, ‘A Brief History of the Word “PREE”’, PREE: Caribbean Writing (17 April 2018), https://preelit.com/2018/04/17/what-is-pree/.